The Samkhya of Kapila has influenced every school of Indian Philosophy. Among the treatises explaining its teachings, only two have survived intact, the rest being either in fragments or totally lost. One of these, the Samkhya-pravachana-sutram with two commentaries by Aniruddha and Vijnanabhiksu form the body of this book, and the others Kapila-sutram, Samkhya-karika of Isvarakrisna and Panchasikha-sutram are given in appendices.

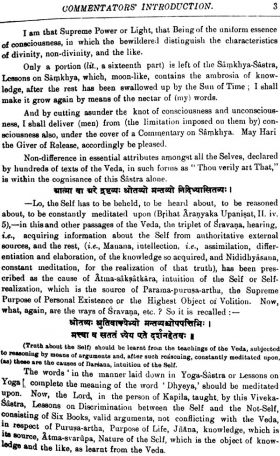

The Samkhya relies on the ruler of logic for establishing the validity of its tenets. Its object is to differentiate between the soul and the non-soul. It starts with the primordial cause called Prakriti or Pradhana which resulted in effect, this world. It has put forward a theory of evolution to explain all objects, animate and inanimate, of this world as an infinite number of permutations and combinations of the three gunas-sattva, rajas and tamas. Its essence consists of two principles: Prakritti and Purusa. It opposes Vedic sacrifices but not the Vedas. It does not deny God but states that His existence cannot be proved. Its importance can be gauged from the fact that the Vedantasutra devotes sixty out of hundred and three aphorisms to refute its doctrines.

The appendices provide all the available texts with indices for aphorisms and words. The translation, with its lucid explanation of the texts and commentaries, brings the Ideas of the renowned Samkhya within reach of all.

Preface

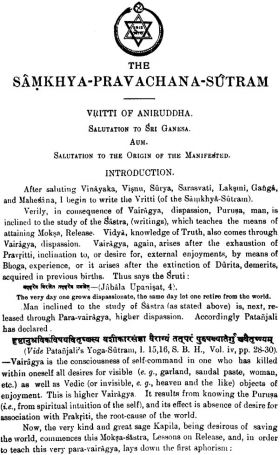

The present volume of the Sacred Books of the Hindus which bears the modest title of the Samkhya-Pravachana-Sutram, is in reality, a collection of all the available original documents of the School of the Samkhyas, with the single exception of the commentary composed by Vyasa on the Samkhya-Pravachana-Yoga-Sutra of Patanjali. For it contains in its pages not only the Samkhya-Pravachana-Sutram of Kapila together with the Vritti of Aniruddha, the Bhasya of Vijnana Bhiksu, and extracts of the original portions from the Vrittisara of Vedantin Mahadeva, but also the Tattva-Samasa together with the commentary of Narendra, the Samkhya-Karika of Isvarakrisna with profuse annotations based o the Bhasya of Gaudapada and the Tattva-kaumudi of Vachaspati Misra, and a few of the Aphorisms of Panchasikha with explanatory notes according to the Aphorisms of Panchasikha with explanatory notes according to the Yoga-Bhosya which has quoted them. an attempt, moreover, has been made to make the volume useful in many other respects by the addition, for instance, of elaborate analystical tables of contents to the Samkhya-Pravachana-Sutram and the Samkhya-Karika, and of a number of important appendices.

In the preparation of this volume, I have derived very material help from the excellent editions of the Vritti of Aniruddha and the Bhasya of Vijnana Bhiksu on the Samkhya-Pravachana-Sutram by Dr. Richard Garbe, to whom my thanks are due. And, in general, I take this opportunity of acknowledging my indebtedness to all previous writers on the Samkhya, living and dead, from whose writings I have obtained light and leading in many important matters connected with the subject.

An introduction only now remains to be written. It is proposed, however, to write a separate monogram on the Samkhya Darsana, which would be historical, critical and comparative, in its scope and character. In this preface, therefore, only a very brief account is given of some of the cardinal doctrines of the Samkhya School.

The Law of the Identity of Cause and Effect

The first and foremost among these is the Sat-Karya-Siddhanta or the Established Tenet of Existent Effect. It is the Law of the Identity of Cause and Effect : what is called the cause is the unmanifested state of what is called the effect, and what is called the effect is only the manifested state of what is called the cause; their substance is one and the same; differences of manifestation and non-manifestation give rise to the distinctions of Cause and Effect. The effect, therefore, is never non-existent; whether before its production, or whether after its destruction, it is always existent in the cause. For, nothing can come out of nothing, and nothing can altogether vanish out of existence.

Definition of Cause and Effect

This doctrine would be better understood by a comparison with the contrary views held by other thinkers on the relation of cause and effect. But before we proceed to state these views, we should define the terms "cause" and "effect." One thing is said to be the cause of another thing, when the latter cannot be without the former. In its widest sense, the term, Cause, therefore, denotes an agent, an act, an instrument, a purpose, some material, time, and space. In fact, whatever makes the accomplishment of the effect possible, is one of its causes. And the immediate result of the operation of these causes, is their effect. Time and Space, however, are universal causes, inasmuch as they are presupposed in each and every act of causation. The remaining causes fall under the descriptions of "Material," "Efficient," "Formal," and "Final." The Samkhyas further reduce them to two descriptions only, viz., Upadana, i.e., the material, which the Naiyayikas call Samavayi or Combinative or Constitutive, and Nimitta, i.e. the efficient, formal, and final, which may be variously, though somewhat imperfectly, translated as the instrumental, efficient, occasional, or condition a, because it includes the instruments with which, the agent by which, the occasion on which, and the conditions under which, the act is performed. Obviously there is a real distinction between the Upadana and the Nimitta: the Upadana enters into the constitution of the effect, and the power of taking the form of, in other words, the potentiality of being re-produced as, the effect, resides in it; while the Nimitta, by the exercise of an extraneous influence only, cooperates with the power inherent in the material, in its re-production in the form of the effect, and its causality ceases with such re-production. To take the case of a coin, for example: the material causality was in a lump of gold; it made possible the modification of the gold into the form of the coin, it will remain operative as long as the coin will last as a coin, and after its destruction, it will pass into the potential state again; but the operation of the Nimittas came to an end as soon as the coin was minted.

Similarly, the Samkhyas distinguish the Effect under the twofold aspect of simple manifestation and of re-production. Thus, the coin is an instance of causation by re-production, while the production of cream from milk is an instance of causation by simple manifestation.

Theories of the Origin of the World

Now, as to the origin of the world, there is a divergence of opinion among thinkers of different Schools : Some uphold the Theory of Creation, others maintain the Theory of Evolution. Among the Creationists are counted the Nastikas or Nihilists, and Buddhists, and the Naiyayikas; and among the Evolutionists, the Vedantins and the Samkhyas the Nastikas hold that the world is non-existent, that is, unreal, and that it came out of what was not; the Buddhists hold that the world is existent that is, real, and that it came out of what was not; the Naiyayikas hold that the world is non-existent, that is, non-eternal, perishable, and that it came out of the existent, that is, what is eternal, imperishable; the Vedantins hold that the world is non-existent, that is, unreal, and that it came out of what was existent, that is, real namely, Brahman; and the Samkhyas hold that the world is existent, that is, real, and that it came out of what was existent, that is, real, namely, the Pradhana. Thus, there are the A-Sat-Karya-Vada of the Nastikas that a non-existent world has been produced from a non-existent cause, and of the Buddhists that an existent world has been produced from a non-existent cause, the Abhava-Utpatti-Vada of the Naiyayikas that a non-eternal world has been produced from an eternal cause, the Vivarta-Vada of the Vedantins that the world is a revolution, an illusory appearance, of the one eternal reality, viz., Brahman, and the Sat-Vada of the Samkhyas that an existent world has been produced from an existent cause.

Against the theories of A-Sat-Karya, Abhara-Utpatti, and Vivarta, and in support of their theory of Sat-Karya, the Samkhyas advance the following arguments:

I. There can be no production of what is absolutely non-existent; e.g., a man's horn.

II. There must be some determinate material cause for every product. Cream, for instance, can form on milk only, and never on water. Were it as absolutely non-existent in milk as it is in water, there would be no reason why it should form on milk, and not equally on water.

III. The relation of cause and effect is that of the producer and the produced, and the simplest conception of the cause as the producer is that it possesses the potentiality of becoming the effect, and this potentiality is nothing but the unrealized state of the effect.

IV. The effect is seen to possess the nature of the cause, e.g., a coin still possesses the properties of the gold of which it is made.

V. Matter is indestructible; "destruction" means disappearance into the cause.

- Sinha, Nandalal

- Hardcover

- Dust jacket

Book or product condition in points:

95-100 - like new, in perfect A condition.

80-94 - used, in excellent B condition.

50-79 - used, in good C condition.

30-49 - used, in acceptable D condition.

No posts found